BEALTAINE EXHIBITION

Virtual – May 1 through July 31, 2021

Failte! Welcome!

Welcome to the Bealtaine 3×3 Exhibit, curated by Robin Savage.

Bealtaine means “Bright Fire” and ritualizes the “well”-coming of Summer. Bealtaine welcomes the Light Half of the year – a concept we here in Maine can really understand! Were we in Ireland, we might ascend the Hill of Uisneach in Co. Westmeath recently featured on the St. Patrick’s Festival broadcast from Dublin; or, we might build two bonfires through which to pass for health and protection.

Instead of real bonfires, we welcome you to our two virtual, metaphorical bonfires through which we hope you will pass, safe and well. The Bealtaine Exhibit is comprised of two galleries each featuring three artists. Additionally, you will find one featurette. Gallery One features Sara Weldon, Joe Kelly, and Vincent Crotty. Gallery Two features Syra Larkin, Mary O’Connor, and Paul Mac Cormaic. Like our St. Brigid’s/Imbolc Exhibit, you will find Curator’s Notes for each Gallery in addition to the artworks.

The featurette is Norah McGuinness, a 20th-century landscape painter, designer, and illustrator. Curator Robin Savage offers notes on her work and we welcome you to link to numerous websites where you can view and study her work and life.

Please visit the shop to view additional works and to purchase!

If you missed it, the St. Brigid’s/Imbolc Exhibit is still up for viewing.

Failte – Welcome. And thank you for visiting.

On Display Now

Gallery I

Gallery One, Bealtaine, Curator’s Notes

by Robin Savage

While our last exhibit (St Brigid’s/Imbolc) was about history and Otherness, the Gallery One exhibit of the Bealtaine show is about space. Both are postcolonial in their implications: history and Otherness is obvious in this regard, but the concept of space might be a bit denser in its relation to struggles for autonomy, freedom, and self-representation from mastery of all kinds.

Perhaps it would be best to look at it from another perspective, as it were. To borrow from John Berger, we could say that all of the arts are defined by what they renounce. Sculpture is defined by Time, therefore, as it is not sequential but remains static. Painting is about space, as are all visual 2D arts (printmaking, drawing, collage, etc.). This is so because the 2D aspect of painting and printmaking demands a “spaceless” surface, and artists must wrestle with the spaces they construct within the flatness of the piece. Hence, we see linear perspective in Western art history, modernist violations of such space, and contemporary returns to the possibilities of spaces that intersect.

Moreover, the concept of space dominates the dynamics of colonialism, from spaces to conquer and the literal meaning of Imperium (space to control), to the concepts of Exile and Home—both central to postcolonial art and politics. This metaphorical and literal space becomes redoubled in postcolonial 2D art and design: artists construct new spaces in many ways related to, and extending, political redefinitions of communities.

Minimalism is also about space, in a way. Because minimalism works to accentuate NOT the idea of using the “least”, but instead the concept of “enough”, minimalist artists highlight the concept of space at the heart of 2D work, especially design which works largely on the strength of space and line. As such, space is the main actor in minimalism, and the “empty” or “negative” space becomes more crucial than the space defined as form. The Empty is really very Full, in other words. And if we conceive of Minimalism as a movement dedicated to renunciation–to renouncing everything that is not necessary for legibility–than we have an art built on a relation between enough and what surrounds it. IT is not as simple as we think in our popular imagination, therefore. Minimalism is anything but minimal.

In Irish and Irish American art and design, space takes on the added dimensions mentioned in postcolonial struggles. It is a heightened concept. In Irish modernism (Jellet, LeBrocquy, McGuinness, etc.), such a play with space and perspective continues the work of 20th century cubism, and in doing so weds itself to internationalism and to what critics call an “alternative modernism.” Such modernisms pervade the postcolonial art world, often contending against realism for dominance. And though Irish modernism did not reach historical fulfillment in Ireland, I would argue that such “alternative” renderings of space did. So that Irish art and Irish American art share this language of spatial play, and any minimalist work compounds that play rather daringly.

Such is the case with the three artists presented in our Gallery One exhibit: Joe Kelly, an Irish American cubist; Sara Weldon, an Irish minimalist designer; and Vincent Crotty, an Irish-in-America “realist” and traditionalist. What I find fascinating in the juxtapositioning of these artists is represented in their spatial relationships just mentioned.

In terms of the three phases of the Irish diaspora, they form a bridge. In terms of their particular “styles” or modes, they do as well…and that might be more difficult to see at first. But look at Vincent’s expert brushwork closely. There is a great deal of suggestion in his work—the suggestive stroke that does not fully render any form. Indeed, Crotty leaves such forms “open” to suggestion in the mind of the viewer to fully define its form. These strokes are about approximation and suggestion. They are Paradigmatic rather than Syntagmatic—they read openly, like poetry, in their associations. Like Weldon’s geometric abstractions and Kelly’s cubist figuration, they invite the viewer to participate and connect possible meanings. Or rather, they give us the space in which to do so.

All three artists in our exhibit are magicians of space, constantly making us question our own spaces, our own edges, our own “enough.” And that, I believe, makes for a powerful and enlivening show that can possibly open up new spaces for our imaginations, our struggles, and our collective being.

[/el_modal_popup]

Joe Kelly

Massachusetts

Sara Weldon

Dublin

Vincent Crotty

Boston

On Display Now

Gallery II

Gallery Two, Curator’s Notes: Syra Larkin, Paul Mac Cormaic, Mary O’Connor

This group of three artists, unlike the Weldon/Crotty/Kelly group, cannot be bound under a single defining theme, style, or ethos. All three paint or create in diverse ways, and seemingly about diverse themes. Yet, taken together, they all do seem to involve deep meaning and significance, often revolving around the land and human community or communion with that land.

Syra Larkin’s work is strongly lyrical and allegorical, as she herself notes, and her paintings often conjure a symbiotic relationship between people and the natural world/environment. Her paintings in this show demonstrate this symbiotic communion through the relation of figures to their surrounding space, a relation that is co-eval. That is, her figures seem to be shaped by the space around them just as much as they actively shape that space. Thus, curvilinearity and color provide a sense of inclusion and deep interdependency that I believe marks all of her work in some way. Wanting to remain open and not be pinned down by any dominant mode or style, Larkin’s work always seems to find a way to heighten this sense of interdependency, of community with the natural world and with the humanity of the cultural world.

Mary O’Connor’s work also emphasizes, though in contrasting ways, this relation of humans to the environment. Her prints enact abstract relations of the elemental forces of the natural world, in my critical assessment at least, and that relation makes them somewhat akin to Larkin’s work. Non-figurative abstraction takes the place of allegorical figuration here, but there is still a quasi-Romantic celebration of the natural environment at play, and O’Connor’s colors emphasize that celebration as do her overlapping transparencies. The shapes of her prints co-exist in a harmony and balance quite subtly profound, and as they re-compose themselves together in the field of vision, they become other objects altogether, forming a new world of sorts. This type of ontological re-composition of objects highlights the more profound aspect of O’Connor’s work for me: a sighting of a new being born out of composite meanings, composite beings, and composite selves.

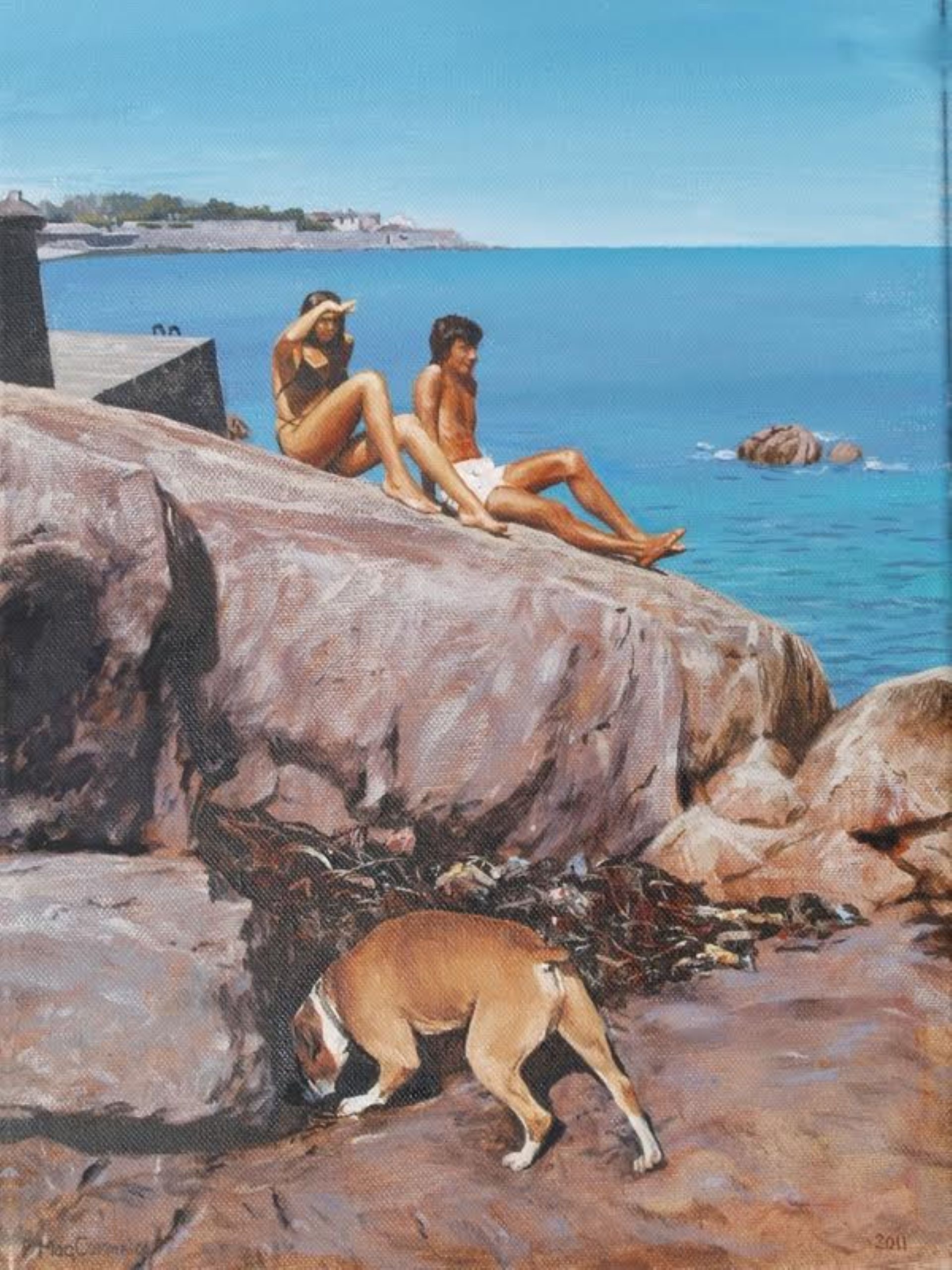

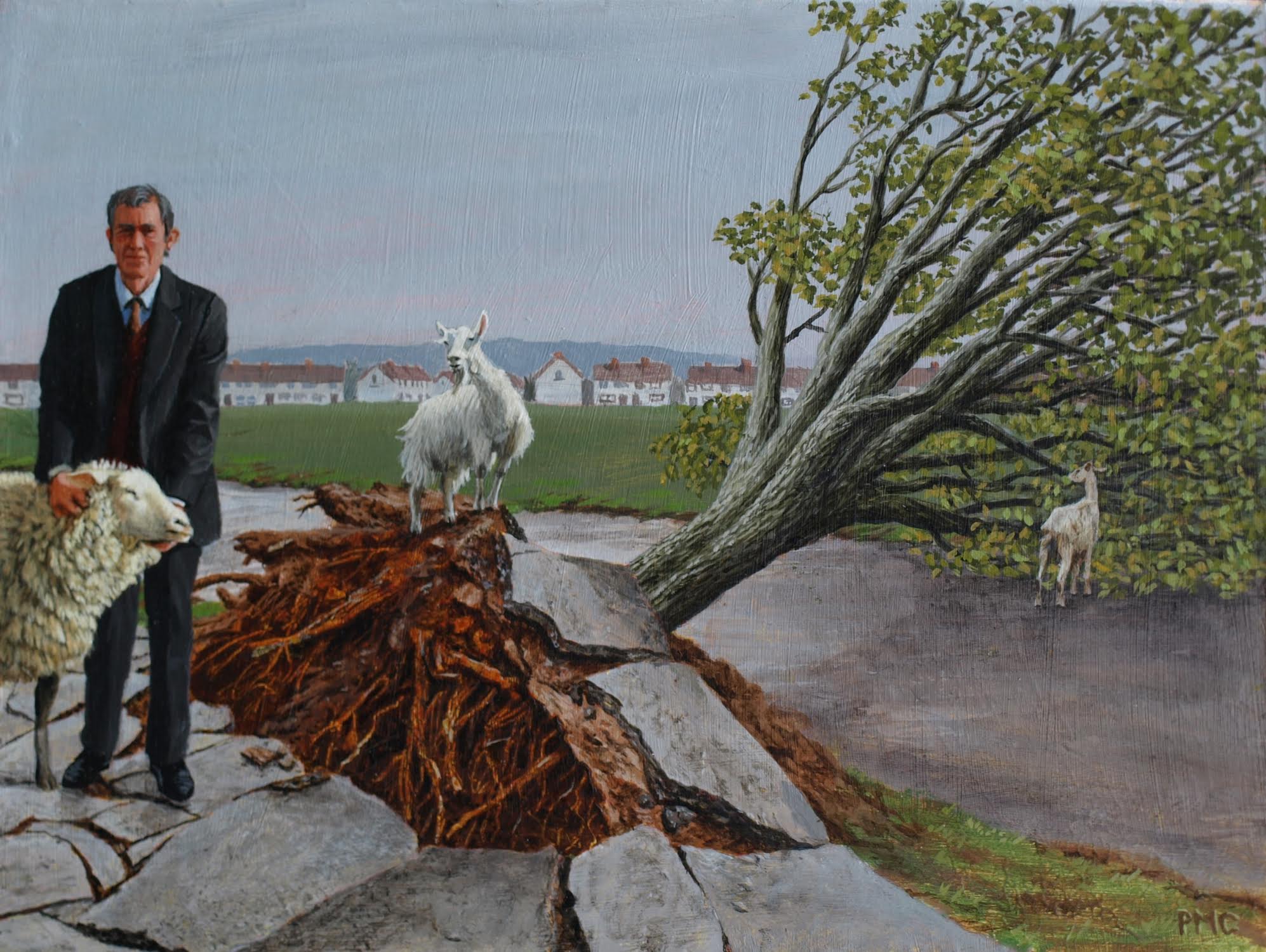

If Larkin and O’Connor offer a kind of Romantic re-connection, Paul Mac Cormaic would seem a more Baroque artist, as he himself indicates. Highly cerebral in the best of ways, Mac Cormaic ranges in his work from brilliant trompe-l’oeil still lifes to the more realist genre pieces in this exhibit, all with a high degree of wit and humor that asks us to examine our own expectations of the activity of painting as much as they do the subject matter of those paintings. Semiotic in their play with symbols and signifiers, Mac Cormaic’s work makes us re-consider our relation to painting itself as an environment for meaning-making, and in these pieces in this exhibit, Mac Cormaic even asks us to examine our various “ways of seeing.” Postmodernist in their juxtapositions, whether bird’s eye views or views of the exclusive (suburban) neighborhoods of the stars (I Can See Bono’s House from Here), Mac Cormaic disrupts our complacencies about the overlooked at the same time as constantly referencing art history and popular culture, and even the nuance of power as it applies to what we are allowed to see. If Larkin and O’Connor seem to ask us to re-connect, Mac Cormaic asks us to polish our lenses and re-focus, re-situating us in the playful act of seeing and making meaning. More Baroque than Romantic, then, Mac Cormaic would best relate to Velazquez in his insistence upon deconstructing the myths that blind and bind us, giving us the same new perspective of our environment that his bird’s-eye views of Wicklow and Donegal computer mappings force us to examine. His own comment that he is creating an “anthropology” of contemporary Western cultural history rings true in these paintings as he provides viewers with various examples of popular media for “seeing” how we look at ourselves.

Perhaps one final examination would reveal that all of these three artists represent postcolonial art, regardless of our assignations of “similarities” or “affinities.” All three deal with central concepts in postcolonial cultural consciousness, from ideas of “home” and “space,” to plays with meaning and a kind of meta-representational awareness of painting as “signs in semantic space,” to environmentalism that verges on indigenous relations to the natural world and our interdependencies with it, to connections outside of a strictly Irish milieu and into the Global South. For example, Larkin’s work may have a connection to European expressionism, but I can’t help but see solidarities with RC Gorman (a Dine’ [Navajo] artist in the US) in Larkin’s circular compositions, and her yearning for communion with the natural world has numerous echoes in an indigenous traditional knowledge. Paul MacCormaic’s work similarly extends out of Irish cliches and into deconstructions of the Empire of the Image throughout European art history. And Mary O’Connor’s abstractions of elemental landscapes seem to re-invigorate the St. Ives school, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and particularly Patrick Heron all at once, while also fully in dialogue with indigenous “mappings” of the environment from Australian Aboriginal art to First Nations art in North America. Such transcultural movements “outward,” intersecting with other Others, is what makes Irish visual art so dynamic in our time, and what will guide it into the future.

[/el_modal_popup]

Mary O’Connor

DUBLIN

Paul Mac Cormaic

Kilbarrack

Syra Larkin

The Maharees

Joe Kelly

I put great importance to freedom and individuality – both in creativity and in life. I try to create thoughtful, high-energy abstract paintings. I use combinations of vivid colors and expressive brush strokes to create vibrancy, dynamism, and a sense of optimism. Painting is the very act of self-expression, the very act of creating that enriches our lives for the better. It’s the communication of intimate creations that cannot be faithfully portrayed by words alone.

[/el_modal_popup][el_modal_popup modal_id=”kelly” trigger_element_type=”image” trigger_image_alt=”JoE Kelly” close_on_esc=”on” modal_title=”Artist’s Statement” _builder_version=”4.9.4″ _module_preset=”default” modal_title_text_font=”Prata||||||||” text_orientation=”left”][/el_modal_popup]

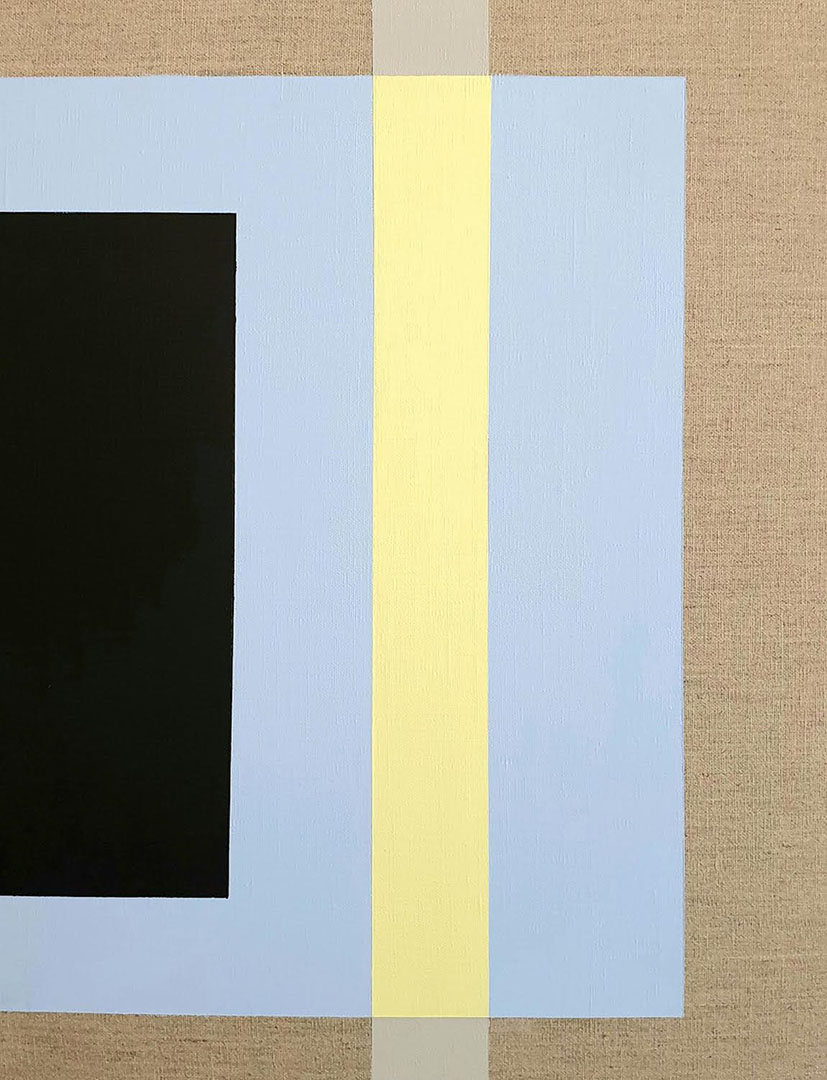

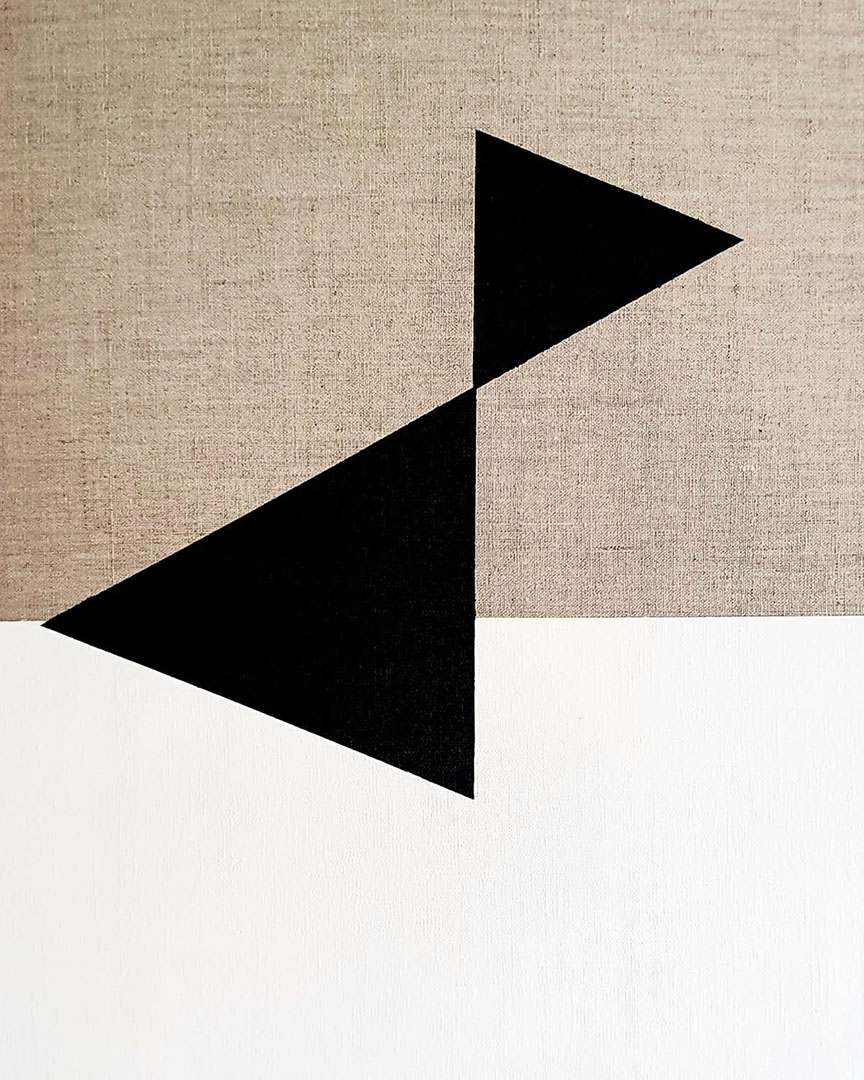

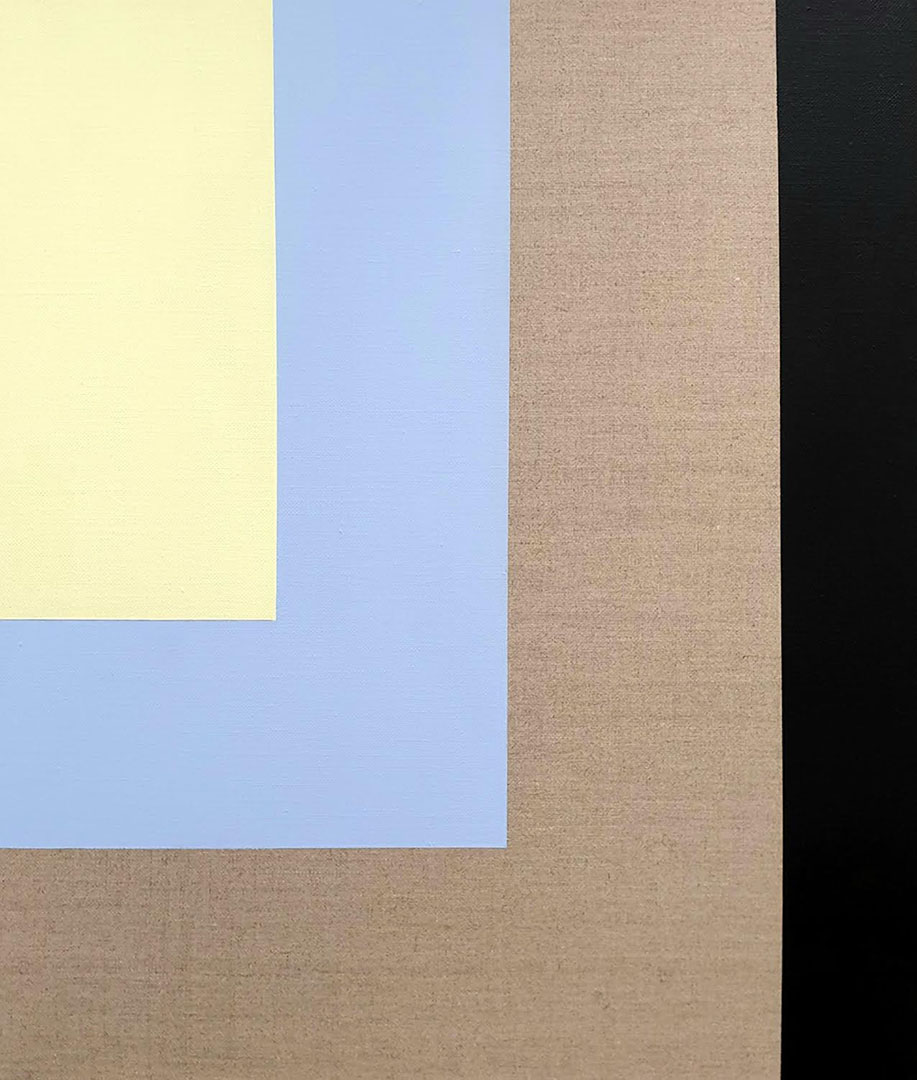

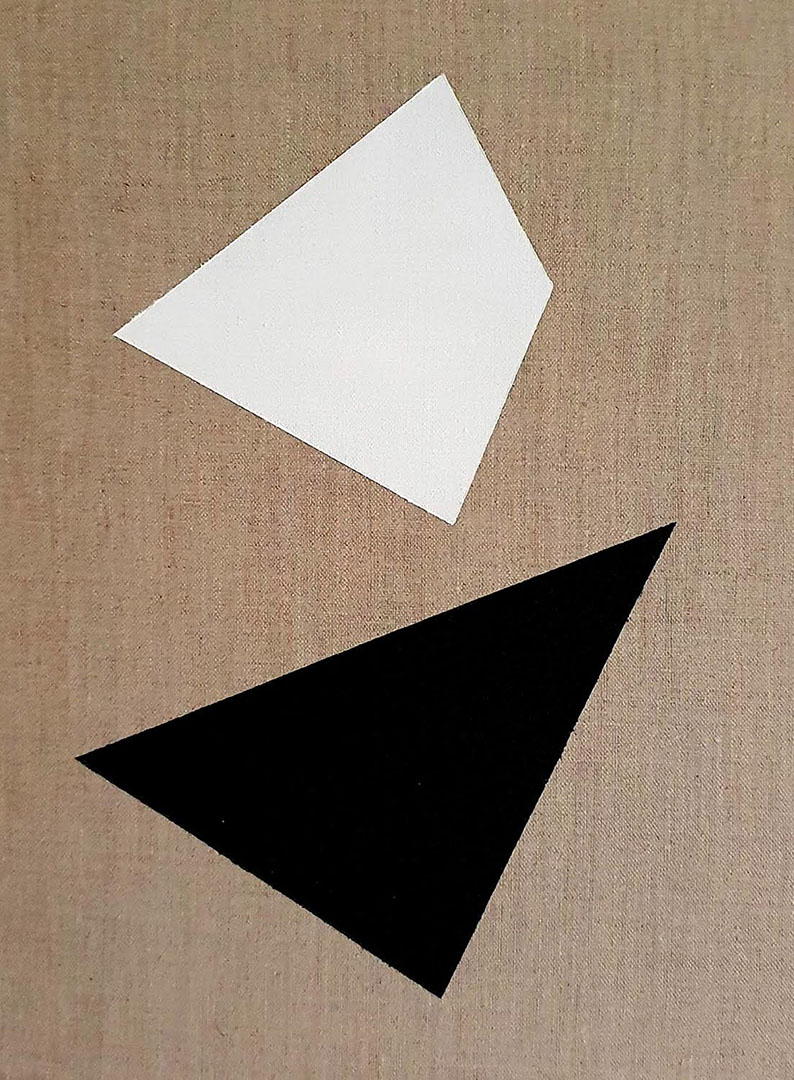

Sara Weldon

“I’m inspired by the contrast between order and chaos, and the illusion of control. My work is primarily focused on those concepts. Structure contains so much internal disorder that is not inherently visible without dissection and is so much more fragile than it appears.

I believe that geometry and shape can describe the emotive elements of the human condition, with the same intensity as any other form of expressive art.

When I begin to sketch a design, I list the various elements that have motivated me to create the image, the message I want to convey, and my palette is based on that psychology. I love to hear how the viewer relates to the work, and what they see inside all those lines and forms, it’s always surprising and hugely gratifying.”

About Sara Weldon

Sara Weldon is a graduate of NCAD and Griffith College, Dublin, Ireland.

Her photography and artwork have featured in numerous publications such as IMAGE magazine, Hot Press magazine, and LIFE Sunday.

[/el_modal_popup]

Vincent Crotty

Vincent Crotty was born and raised in Kanturk, County Cork — a small town in dairy farming country in southwest Ireland who has been living in Boston since 1990. Regarded for his landscapes, seascapes, nocturnes, and figurative paintings, he paints with fluid and vigorous brushstrokes, balanced by sensitive color. His paintings reveal a remarkable understanding of light — transforming everyday subject matter into images that are memorable and moving.

Exhibiting his work for over 35 years, with gallery shows in Ireland and throughout the US, his painting has been recognized with awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the John Stobart Foundation, Plein Air Magazine, and plein air competitions internationally.

In addition to his gallery shows, Vincent’s paintings have been featured as set designs for theater companies and touring productions including Atlantic Steps, the Cork City Ballet, the Huntington Theater Company, Kieran Jordan Dance, and the WGBH Celtic Sojourn productions. Four of his paintings were used on the film set in the 2003 Clint Eastwood movie Mystic River.

Vincent is also well-known for his paintings of Irish traditional musicians. He has painted commissioned portraits of beloved musicians Felix Dolan, Joe Madden, and Larry Reynolds, and has created CD covers for Irish music artists including Joey Abarta, Tim Browne, Marla Fibish, Bridget Fitzgerald, Sean Keane, Ben Power, and the group Childsplay. His large-scale Irish set dancing mural called “Side Couples Swing” hangs as a permanent installation behind the bar in the Irish Cultural Centre of New England.

[/el_modal_popup]

Mary O'Connor

A Visual Painter and Printmaker, Mary has been selected for group exhibitions including the RHA Annual Exhibition, RUA Annual Exhibition, and Cairde. Her work is included in many public and private collections. She has completed a commission for wall murals in Capitol Dock, Dublin. She participated in OVER NATURE, a touring exhibition, and was the recipient of the Galway County Council Purchase prize, Impressions Biennale 2019. Most recently was commissioned for DLR Artworks Home, supported by The Arts Council of Ireland. Her first Solo Exhibition in Dublin, KEEL has just finished at So Fine Art Editions Gallery.

Living in Dun Laoghaire, Dublin. Born in Wexford She studied visual communication and 3D design at TU in Dublin, and painting at Chelsea College of Art, London, and in New Zealand. She also lived in Belize and Kazakhstan, a place of vast landscapes and infinite white winters; during her time there (eleven years) she published two books of photojournalism on Central Asia.

Mary’s paintings and prints are influenced by her surroundings. The vast landscapes encountered on her travels are conveyed through shapes, space, and colours that emerge as non-representational abstract compositions. Cultures, travel, time, memory, and flux are essential elements in her work.

[/el_modal_popup]

Paul Mac Cormaic

My personal vision is to make iconic memorable images that have a universal timeless appeal. The universal themes of love, hatred, justice, ethics, and survival run through my work as a constant narrative. The starting point for much of my work is the powerful imagery of newspapers, TV, and the Internet, especially advertising. In common with much of the art of the post-modern era and indeed dating back to Dada, I use imagery from popular culture as well as direct observation. I filter them and re-present them to make exaggerations and juxtapositions and create a drama that unfolds as the 21st century baroque. My work is often imbued with a sardonic wit. I use realist painting and photography with strong lighting and cinematic angles to create scenarios that form an anthropology of contemporary Western society.

About Paul Mac Cormaic

I was born in Dublin in 1961 and grew up in Finglas, where I lived on the edge of a city and the beginning of the countryside. I now live in Kilbarrack near the sea and have my studio in my back garden. Living in suburbs, as most people do, has given me an ‘in-betweeny’ view of life, neither rural nor city. From a visual arts point of view, the suburbs are often overlooked and so have featured a lot in my work. I resigned from my job in 2001 and became a full-time student at UCD reading History of Art and then went on to IADT in Dún Laoghaire to study Fine Art. I have worked as a professional artist since graduating in 2006.

[/el_modal_popup]

Syra Larkin

As an artist it’s important not to allow yourself to be tied up into a neat package that can be easily understood; as like most things in life, it is not easy to explain or understand the things we create. I do not want to feel the restrictions of a pattern or a particular style—if I want to run I will, if I want to do a summersault I will. I feel my work is a genuine response to my personal existence. Waking in the morning and painting whatever the day might bring!

About Syra Larkin

Syra studied Art at Hammersmith College of Art London and qualified with merit in 1972. In 1977 Syra together with her husband Irish Luthier Chris Larkin (RIP 2018) moved to a small windswept peninsula known as The Maharees on the West Coast of Ireland. Where they lived, worked, encouraged, and inspired one another daily.

Syra lived and worked for many years in a caravan and today works from a purpose-built studio known as Shoreline Studio, where despite the remote location she has managed to develop her career as a professional artist. Taking part in many of the major open submission exhibitions in Ireland and London.

She has had work in both solo and group exhibitions in Ireland, America, Spain, Italy, Belgium, France, and England. Syra’s work was selected for the Inaugural Kerry Visual Artist Showcase in 2015. Sponsored by Kerry County Council in support of The Arts, Syra Larkin’s art is found in both private and corporate collections.

Syra’s work is mainly figurative in style and she would use these words to describe her work: figurative, emotional, poetic, symbolic, mercurial, narrative, eclectic.

[/el_modal_popup]

Featurette

Norah McGuiness

In The Algarve (1961)

Oil on canvas; 28 x 36 in

BEALTAINE EXHIBIT Featurette

Norah McGuinness

I chose to give this exhibit’s featurette to Norah McGuinness for a number of reasons, the best of which amounts to her continuation of the Mainie Jellett inspiration for the CA BHFUIL SINN FEIN exhibit in March 2020 at the Maine Irish Heritage Center. Like Jellett, McGuinness was a modernist Irish painter who studied cubism in France, (Jellet with Gleizes and Lhote; McGuinness with just Lhote apparently) and then transported these cubist leanings back to Ireland and Irish visual art. Both artists contributed a great deal to cubism as well, I would argue, and to Section D’Or and the Ecole de Paris. This is largely because any cursory examination of their work points to a transformation of cubist principles and the Gallic theories of Gleizes into a representational style that morphs cubism’s tendencies toward abstraction back into Irish art history and traditions of design, primarily. So that, Jellet’s work has almost direct reference to Irish penwork and to Catholic architectural and iconographic design features, and McGuinness adds similar motifs and designs from Irish environments and histories. Both, then, participate in an international style and make it simultaneously local, national, even communal in a sense.

The modification of cubism and representation both is mirrored in the French and Irish hybrid. Modernism finds a home in Irish art and Irish art finds a home in Modernism. And though critics add that such Irish modernisms were short-lived, we would be short-sighted to not emphasize the remarkable resistance to conventions and conservatism that both artists enacted.

What adds to that remarkable resistance is, of course, the fact that both Jellett and McGuinness were women. Accompanied by many other women artists, from Evie Hone to Anne Dugan to Nano Reid, these women artists would form the backbone of the Irish artistic revolution in the 1940s and 1950s and beyond. Breaking with the traditional institutions that controlled artistic power in the early 1940s, both Jellett and McGuinness formed the Irish Exhibition of Living Art to combat the limitations placed on Irish artists by the Royal Academy (who ruled that only dead artists could be exhibited). Jellett’s death, a year after founding and serving as President for the group in 1943, made McGuinness the President of the group, and she and Nano Reid would go on to represent Ireland in the Venice Biennale in 1950, the debut of Irish artists in the much-vaunted annual exhibition.

Even more, however, was the work that Norah McGuinness performed for other Irish women artists through the group that she founded with Jellett. Records indicate that, during her tenure, the majority of Irish artists exhibited from 1950 onward were women. Such resistance to the patriarchy has significant implications for the agency and power of Irish artists across gender divides as it demands equality and freedom to choose representation as a right and not a privilege, but it is particularly significant for Irish feminist resistance. The power over representation is the most crucial aspect of such struggles against the mastery of any kind, and the “right to look” cannot be exclusionary if art is to be free.

In this way, Norah McGuinness is not only an Irish artist, a modernist artist, or a woman artist, she is representative of a postcolonial Irish art and culture, one that intersects with feminism, with other Others, and with struggles for the voices of those so long erased in our own time. Norah McGuinness showed us all another way of seeing, and along with other Irish modernists like Louis LeBrocquy, defied our complacencies, our fixed positions, and our entrenched prejudices…

And for that, she deserves the highest honors at Carrickahowley Gallery.

For a sample, or to begin your exploration of Norah McGuinness, click the link to the Irish Museum of Modern Art Norah McGuinness page:

https://imma.ie/artists/norah-mcguinness/

[/el_modal_popup]

The artworks exhibited here are not for sale. Here you may view historical works, works in conversation with challenging subjects, or works of visual complexity. It is here, in the Featurette Gallery, that you will encounter the larger spectrum of issues relating to Irish and Irish American art as well as intersectional art that may challenge our perspectives around the histories that we share with others.

Carrickahowley – What’s in a Name?

Carrickahowley is in County Mayo, Ireland, and is the historical site of the stronghold castle of Grace O’Malley, or Grainne Mhaille. Grace O’Malley was a seventeenth-century pirate queen of Western Ireland who led an entire fleet of ships over her long career and met Queen Elizabeth I in a historic meeting. The name references many things, therefore, from respect for women in Irish history to fierce independence and capable leadership.

The stronghold and its location conjure the rocky coast of Maine, with its opening to the Atlantic Ocean that separates Ireland from Maine.

Fine Art & Prints

Carrickahowley Gallery

Support the bridge between Irish and American art by shopping at the Carrickahowley Gallery. You’ll find prints and original art at affordable prices. Plus, a portion of the proceeds benefits the Carrickahowley Art Gallery and our mission.